Return to Specifications Grading

I’ve had a lingering “to be continued” here for a few months, as I promised to report on my experiment with specifications grading from the spring, beyond my first mid-semester update. The delay was first due to the need to wait to process a post-semester survey that we did from my class and another colleague who used a similar approach to grading. Once we got those results, my head was already deep into summer mode of writing deadlines and family fun. But now on the eve of my fall semester starting, I’m ready to return to the classroom and the topic of grading.

In short, all evidence suggests that my experiment last semester was a success, and I’ll be using a similar approach to grading this fall in my course, Theories of Popular Culture. I’ll detail some of my revisions to the approach as customized for that course – a writing-intensive upper-level seminar of 15, rather than an intro-level survey of 30+ students – in another post. But here I’d like to explore how my Television and American Culture course turned out, and offer some reflections on the benefits and limitations of specifications grading.

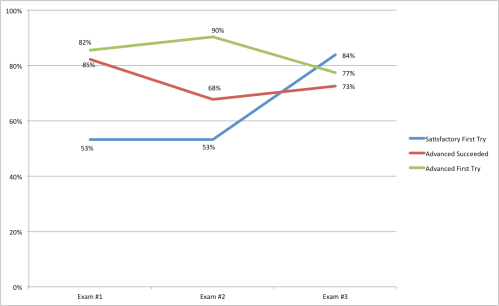

One of the data points I mentioned in my mid-semester update was that around 60% of my students had to revise at least one of the two exam questions on the first midterm, a fact that I attributed to students learning to calibrate to my expectations. Looking over the course of the semester, this seems only somewhat true. Here is a graph of the three exams, each of which contained two mandatory questions (each with Basic and Advanced level options); the graph tracks the percentage of answers that met Satisfactory on the first try, percentage of answers that strived for Advanced on the first try, and the percentage of answers that were eventually Advanced Satisfactory on each exam (the final average was that each student did 4.45 Advanced Satisfactory answers within the course; 2/3 of the students fulfilled the 5 or more Advanced answers needed to earn an A):

What this suggests is that the success rate for Exam #2 mirrored the first exam, a result that is best explained via two factors: a higher number of students aimed for Advanced answers on Exam #2, making it more challenging, and one of the Advanced questions on Exam #2 proved to quite challenging (everyone aimed for Advanced on this question, but only 39% succeeded on the first try). Many of these students downgraded to the Basic question, which did not necessarily undermine their final grade possibilities, providing the flexibility and self-guidance that the system strives for. The stats on the third exam do suggest that students learned how to succeed on the first try quite well, although they also aimed lower, in large part because they had already fulfilled sufficient numbers of Advanced answers to receive the grade they were aiming at. One aspect I did notice that was an issue is that due to the flexibility of revisions built into the system, some students purposely handed in incomplete or underdeveloped work as a “rough draft” rather than a completed essay, a tendency that encouraged procrastination and deferring of work until later in the semester. I’ve tried to adjust my revision system to curtail such tendencies in the new course.

One of the most interesting results concerned the final essay. As the assignment aimed at the course’s highest level of learning goals, it was completely optional to complete, required only if the student wanted to be considered for a grade of A or A–. With that choice available, virtually half of the class opted not to do the essay. Their reasons ranged: some had not completed the required exams and/or screening responses needed to qualify to get an A, and therefore they chose not to put in the extra work at the end of the semester. Others were well-poised to get an A, but found themselves overwhelmed with work and decided to take advantage of the flexibility to opt into getting an assured B+ in the course—a couple of students reached out to say that such flexibility was crucial in helping them succeed in the full balance of their course loads.

Of the 16 students who did submit final essays, 10 reached the threshold of Satisfactory, with many very strong essays that would have received an A in my traditional schema. Notably, a few students sent me early drafts for feedback and revision to reach that mark — one student embraced this revision process so fully that she wrote five drafts to continuously improve her work! Four students wrote essays that fell just short of the specifications, but had they gotten Unsatisfactory, their grades would have been B+ instead of an A for reaching Satisfactory. For those, I split the difference and gave them an A- in the course with partial credit for the essay, as that felt like a fairer assessment of their work. Thus one lesson for future iterations of the class is to highlight that such high-impact “all or nothing” grades can be given partial credit in some instances.

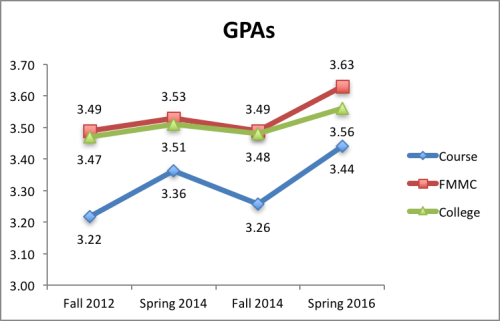

In launching this experiment, I had assumed that the course’s overall grades would decline, as it raised the bar for both passing and getting a B compared to previous years. But I was wrong: the course’s overall GPA of 3.44 was actually the highest it has ever been. This chart compares the course’s GPA in each recent semester it has been offered to that semester’s college-wide GPA and my department Film & Media Culture (FMMC), which usually has a slightly higher GPA than the college average (although lower than most other arts and humanities departments). While my course had a record high GPA, so did my department and the college, so it’s hard to disentangle these data.

The more interesting aspect of my course’s GPA is the actual breakdown of individual grades, as compared to other semesters:

The most significant differences here certainly concern the number of A grades earned by students: 9 A’s was unheard of for my typical grading, as I tended to reserve A for students whose work “sparkles” and is remarkably consistent. But could I really explain to one of the 20 students who received an A- in my course in 2014 what they would need to do to earn an A? Probably not, as that designation was typically a “know-it-when-I-see-it” type of accolade.

But last spring, I laid out very clear specifications as to what it would take to earn an A, and 9 students worked hard and demonstrated that they had learned enough to earn that achievement. Looking back, I can say that it is likely that 5 or 6 of those students would have earned an A under my conventional grading system, as I had an unusually strong class (although as I said in the last post, much of that would have been rewarding what those students brought to the class in terms of background, talent, and experience knowing my preferred style of writing and analysis, rather than what they learned in the course). A couple of the students who earned A’s in the spring did not do so by producing conventional “A work”—they did not “sparkle.” But they met all of the expectations I laid out for the course, worked consistently hard to meet those goals, and clearly demonstrated that they learned a lot throughout the process—perhaps they learned even more than the students who came into the class highly prepared to succeed. So I feel quite comfortable having given an A to a student who did not do conventional “A work,” and might have earned a B+ or A– in a conventional system.

Looking at some of the B or lower grades (which are consistent as 30% of the course in each semester), I think those were often highly successful learning experiences as well. Some were more about meta-practices of education, in terms of prioritization, time management, and self-awareness of their own strengths and limitations as a student—those students who actively chose to aim for a B or B+ in order to put more time into another course surely were happy with that option. One student struggled quite a bit on the first two exams, needing to revise every question (some multiple times) and seemed not to always be aware of his own writing practices; however, it clicked for the third exam, where he completed both Advanced questions to a Satisfactory level successfully on the first try, learning how to put the necessary time and care into his own work. That was a B as a marker of successful learning.

From my perspective, I look at my roster spreadsheet, and feel more confident than any other semester that each student got the grade that they earned, and maximized their learning to correspond with their chosen effort. To me, that’s a huge success of a semester! But what did the students think?

I think traditional student evaluations are a nearly useless measure of student learning, but our office of institutional research helped design a more useful survey for students in my course and that of my Computer Science colleague, Pete Johnson, who also experimented with specifications grading. Overall, responses were positive for both courses—the majority of students agreed with various positive statements asserting that this system provided flexibility and clarity, emphasized engaged learning, and reduced stress, with flexibility getting the strongest support among these facets. Very few respondents suggested that specifications grading would discourage them from taking a course in the future, while a majority said it would make them more likely. Here are some choice comments from the survey’s qualitative responses:

- “I approached the course more confidently because I knew exactly how everything added together and I had agency in that.”

- “I was completing things as stepping stones to my grade rather than focusing on them as individual assignments.”

- “I told many of my friends over the year about the grading system. I told them that it basically allowed you to choose at the beginning of the year how much you care about the class, due to the bundle systems.”

- “It helps you prioritize the assignments you want, and it clarifies exactly what you have to do in order to get a grade. It makes the grading system feel less arbitrary and like you have more control over your final grade.”

- ” I found it incredibly helpful that Professor Mittell understood that students are taking many classes and TVAC may not be the priority at that point. I think he used it to better set us up to succeed, whatever that means to us. I really appreciated this system and wish it was standard.”

- “I think Prof. Mittell wanted to increase the transparency of grading standards and level the playing field for students who hadn’t taken previous courses in film (or were less familiar with college level writing).”

- “I think Professor Mittell was attempting to lower the pressure associated with performing well in a class at Middlebury, both for the students and him as the professor.”

- “I choose not to do the final and I do not regret this. I did not get the A, but I got a B+ without the stress of a final. I think it was an even trade.”

There were two threads of comments that were more critical of the system. The first was that the standard for Satisfactory was too high, with students feeling like they had to keep revising their work to meet unreasonably high expectations. I’m comfortable with this critique, as I can easily show any student where their Satisfactory work may still be below an “A” paper, and that such revisions help them learn—and it’s a universal truth that no matter what the standard, somebody will complain that I’m too hard of a grader!

The second critique is the opposite and more tricky: concern that Satisfactory is too broad, discouraging high achieving students from reaching for excellence. Some good quotes:

- “My only concern is that this system encourages quantity more than quality. It cannot distinguish a phenomenal work from a good one. ‘Remarkable’, ‘great’, ‘good’ and ‘acceptable’ are all on the same level and graded in the same way: ‘Satisfactory’.”

- “I think one problem with the specifications system is that for the not overly advanced assignments it encourages A-students to lower their work standards because they know they just have to do satisfactory work and not exemplary work on that individual assignment.”

This is a fair critique, especially for courses beyond the 100-level. Personally, I think there were very few instances of students aiming low but still succeeding. Certainly some aimed higher without real rewards in the grades: four students opted to complete all 6 exam questions at the Advanced level, even though only 5 Advanced were required for an A. And none of the final papers that met the satisfactory specifications read as being lazy or underdeveloped in any way, suggesting that “lower work standards” was not much of an issue.

However, I do think this concern of not motivating the best work does matter more in upper level courses, where excellence and greater depth is more possible and vital to many students’ learning. Another concern that I’ve tried to address is that in-class participation did not count in student grades, so there was little motivation for students to engage (besides, you know, learning). In the next post, I’ll talk about how I addressed both of these concerns in my current course.

Filed under: Academia, Middlebury, Teaching | 1 Comment

Tags: specifications grading

One Response to “Return to Specifications Grading”